There are no upcoming events in this category

Friday

December 26

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

Saturday

December 27

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

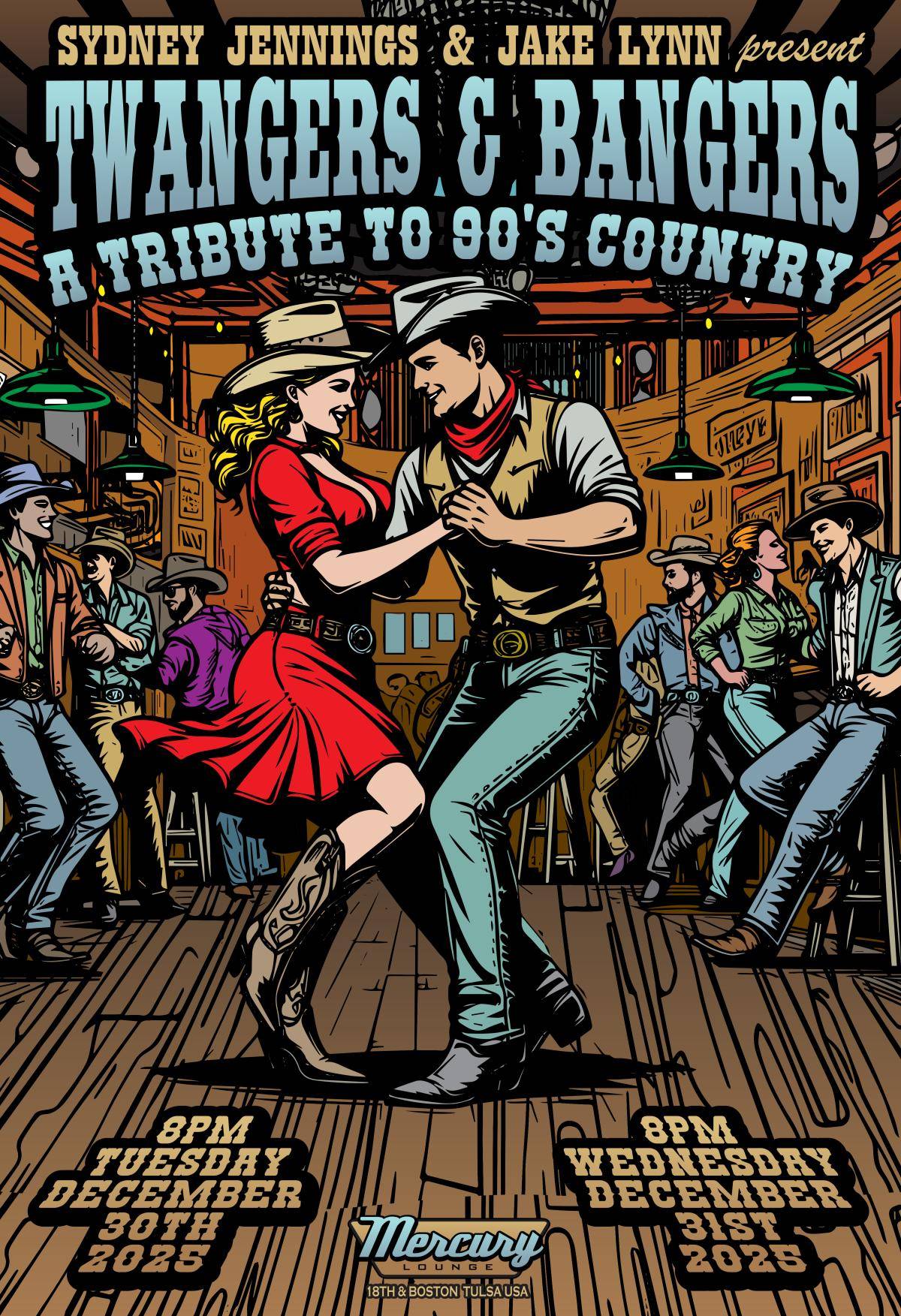

Tuesday

December 30

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

Wednesday

December 31

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

Sold Out

Friday

January 2

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

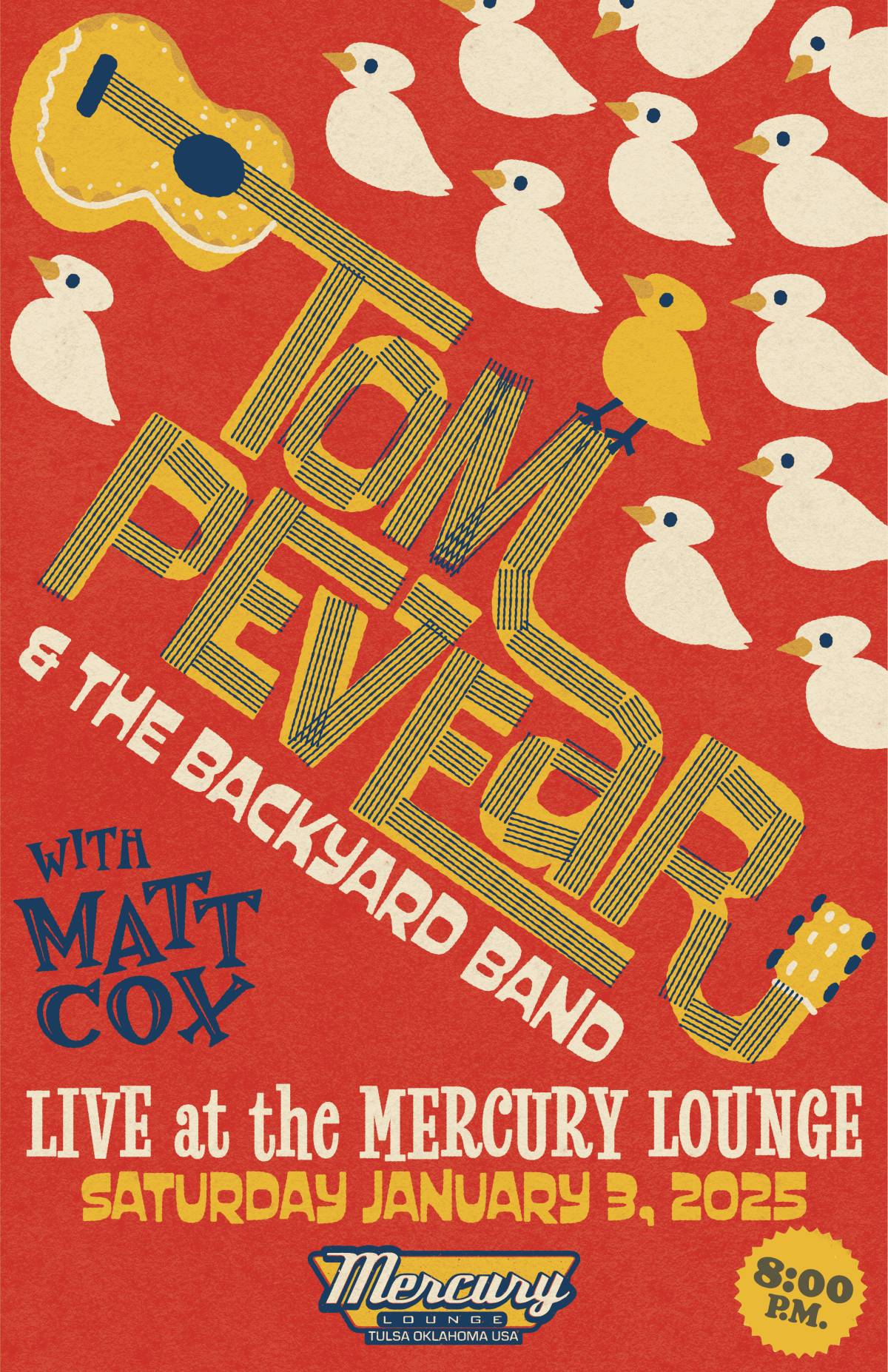

Saturday

January 3

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

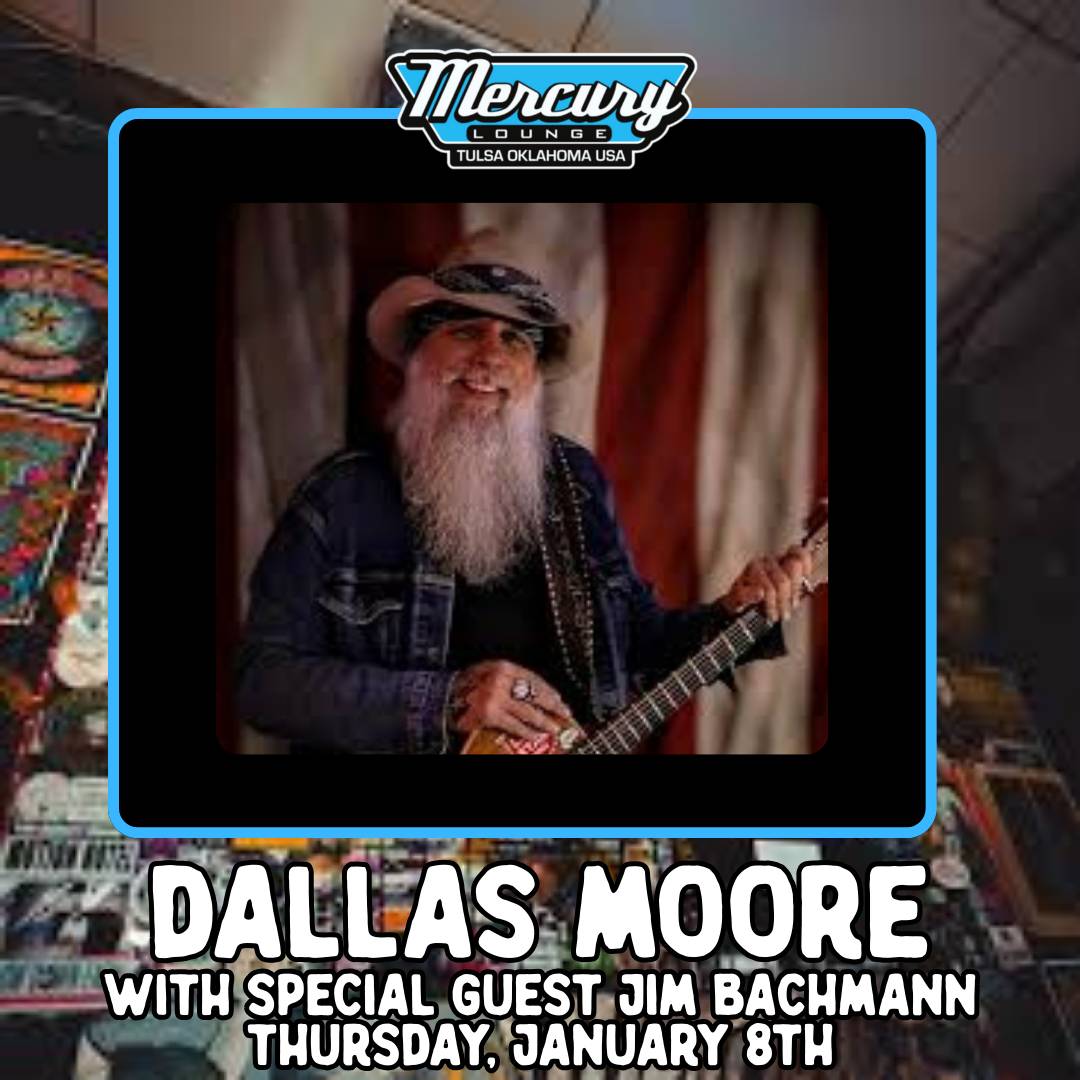

Thursday

January 8

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

Friday

January 23

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK

Friday

February 27

Doors 7:00pm, Start 8:00pm

Mercury Lounge

-

Tulsa, OK